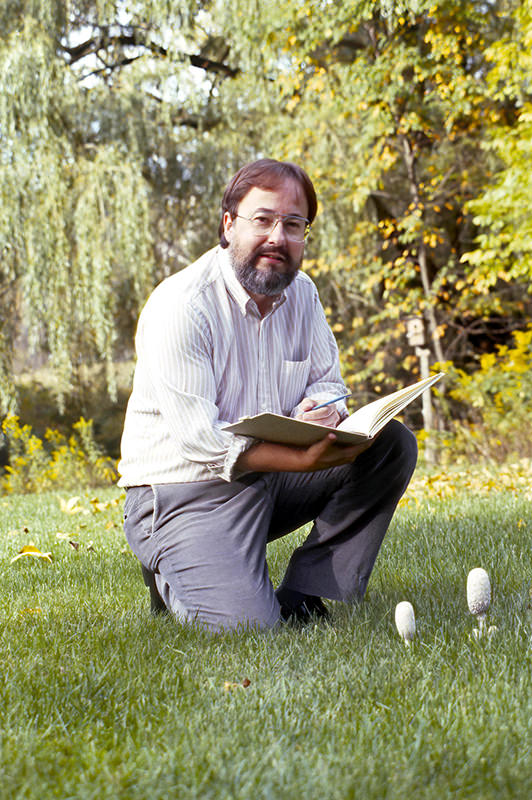

is a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the Explorers Club. Born in 1945, Loates began his professional career at the age of 11, when he designed the Canadian Cancer Society's daffodil logo, used for several decades. In 1964, he had his first one-person show at the Royal Ontario Museum. In 1968 he won the Royal Philatelic Award for Canada's first full-color postage stamp, the "Gray Jay." He has also been the subject of several television specials, including the award-winning documentaries "Colour It Living" and "Paint It Wild."

Loates is the first Canadian artist to be represented at the White House. In 1982, The Right Honourable

Pierre Elliot Trudeau arranged for Glen to meet with

President Reagan in the Oval Office to present Glen's painting, "The Bald Eagle" to the American people on behalf of Canada.

Glen's other work was also given to His Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the Right Honourable Pierre Elliot Trudeau, former Prime Minister of Canada.

is a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the Explorers Club. Born in 1945, Loates began his professional career at the age of 11, when he designed the Canadian Cancer Society's daffodil logo, used for several decades. In 1964, he had his first one-person show at the Royal Ontario Museum. In 1968 he won the Royal Philatelic Award for Canada's first full-color postage stamp, the "Gray Jay." He has also been the subject of several television specials, including the award-winning documentaries "Colour It Living" and "Paint It Wild."

Loates is the first Canadian artist to be represented at the White House. In 1982, The Right Honourable

Pierre Elliot Trudeau arranged for Glen to meet with

President Reagan in the Oval Office to present Glen's painting, "The Bald Eagle" to the American people on behalf of Canada.

Glen's other work was also given to His Royal Highness Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and the Right Honourable Pierre Elliot Trudeau, former Prime Minister of Canada.

Loates' accomplishments include the publication of three significant volumes of his work: The Art of Glen Loates (1977), Birds of North America (1979), and A Brush with Life (1984). His art was exhibited in museums such as the Alexander Koenig Museum, the Institute of Zoological Research, the Centre Culturel Paris, the British Museum, the McMichael Canadian Collection, and the Royal Ontario Museum. His work has appeared in numerous North American publications over the years as well as international magazines such as GEO and Reader's Digest.

Throughout his career, Loates worked with several wildlife conservation authorities and many conservation groups. He has also dedicated much of his time to scientific research. In 1986, he was invited to join the

National Geographic Society's Beebe Project in search of giant squid and six-gilled sharks off the coast of Bermuda. Here, along with a team of prestigious scientists, Glen descended in a mini-submersible to depths over 1500 meters to illustrate life far below the surface. This exploration resulted in Loates being commissioned to create a mural depicting 125 different species of ocean life for display at the Bermuda Underwater Institute of Exploration and Research.

Glen Loates continues to produce artwork for private and corporate clients.

The Royal Canadian Mint renders his highly detailed images on collector coins with subjects that depict Canada's natural environment, its wildlife, and Canadian history.

Loates' accomplishments include the publication of three significant volumes of his work: The Art of Glen Loates (1977), Birds of North America (1979), and A Brush with Life (1984). His art was exhibited in museums such as the Alexander Koenig Museum, the Institute of Zoological Research, the Centre Culturel Paris, the British Museum, the McMichael Canadian Collection, and the Royal Ontario Museum. His work has appeared in numerous North American publications over the years as well as international magazines such as GEO and Reader's Digest.

Throughout his career, Loates worked with several wildlife conservation authorities and many conservation groups. He has also dedicated much of his time to scientific research. In 1986, he was invited to join the

National Geographic Society's Beebe Project in search of giant squid and six-gilled sharks off the coast of Bermuda. Here, along with a team of prestigious scientists, Glen descended in a mini-submersible to depths over 1500 meters to illustrate life far below the surface. This exploration resulted in Loates being commissioned to create a mural depicting 125 different species of ocean life for display at the Bermuda Underwater Institute of Exploration and Research.

Glen Loates continues to produce artwork for private and corporate clients.

The Royal Canadian Mint renders his highly detailed images on collector coins with subjects that depict Canada's natural environment, its wildlife, and Canadian history.

When one refers to the exquisite quality of a piece of art, the usual definition of that over-used adjective comes to mind: beautifully made or designed. Applying that descriptive term to the watercolors of Martin Glen Loates is almost a necessity in order to convey adequately the degree of appreciation that his work arouses. However, the word exquisite itself is derived from the Latin exquisite, chosen, exquisite, from the past participle of exquirere, to search out. It is this shade, then, of the word exquisite that makes the adjective singularly appropriate in a more arcane sense to Loates' work. He has searched out and chosen the subtle gradation in color, the elegant rhythm in form and line, the elusive in mood. His Ruby-throated Hummingbird, as light as the pendant columbine blossoms that attract it, is part of the aura of a summer day, and more: it imparts that clean, verdant, colorful sparkle that characterizes what a summer day is. The artist has managed to illustrate, then to evoke, then to invite, finally to captivate.

Loates' common woodchuck, perhaps the pièce de résistance of the show, took this reviewer back in time. In childhood, we lay on our stomachs in summer clover, and some cool, green, crushed-grass deliciousness about that delightfully lazy pastime flooded back, immediately, upon seeing this brown, furry fellow standing in the grass, his black front toes clasping a crisp leaf. Many visitors to the exhibit commented on the fur – rich, thick, rendered perfectly, golden brown about the shoulders, greyed out from his whiskered nose, and forming an easily recognizable whorl down the center of the abdomen. Passing a hand down that soft belly, one would enjoy those fine thistle-down patterns of fur. Art, good art, encourages the viewer to imagine tactile possibilities. (The likelihood that the woodchuck would permit such familiarity belongs to another discussion.) Some zoologists have commented that Loates' mammal paintings are among the best they have ever seen. One of the nicest things about his way with mammals, incidentally, is his shrewd ability to avoid the "cute." To do this, one must know the animal very well, paint it accurately, allowing it the dignity of its usual activities, such as standing in a patch of grass eating a leaf, rather than portraying an antic pose that is more beguiling and less characteristic. Loates' pencil drawing of a Ruffed Grouse shows this game bird in his most dramatic moment: his neck feathers raised in a ring about his head, his tail erect like a turkey cock's, his mien admirably commanding and threatening as he mounts his drumming log. Loates uses soft pencil well and proves that black and white can be more colorful than color. The challenge in this medium is to use shadow, light, coarseness, delicacy, and roughness in a kind of orchestration that satisfies so sensually that color would be redundant. In central New York, the Northern (Baltimore) Orioles usually arrive in early May. Glen Loates has painted a pair of these familiar birds, known for their craftsmanship in nest-building. Perched at their pendant nest in the drooping branches of a tree, the pair is caught in the midst of brisk business – nest building. Later, they will browse for their food near the ground and on lush clumps of sweet fern. The underside of the male is bright orange, changing to an ochre color just under the rump. The female wears more subdued colors, her yellowish olive upper parts not so sartorially exciting as the sharp black uppers of her mate. Melodious describes the interplay of colors and tones in this watercolor: Pale, pale green leaves twist to give us deeper green shadows. We rivet upon the vibrant orange of the male, go on to the incredible intricacy of the soft gray nest that occupies the center of the painting, read the female as a more restrained accent in her olive green and dull orange. A caterpillar, later destined to be an oriole's meal, has done a random job on the leaves of this hanging branch. These holes are carefully observed, delineated as painstakingly as the coverts on the birds' wings, and treated as important elements in the total design. The white background of the painting is put to work by the laced leaves, not by accident but by conscious manipulation of negative spaces. Good designers may become great artists; great artists are always good designers. Without going into more detail, Loates' show includes a very small painting of a Snow Goose landing; there is a shadow in the softest shade of gray, cast by its strong neck against the straining pectoral muscles as it comes down to land, which is typical of Loates' meticulous observation and technical proficiency. The effect of the gray shadow is evanescent. It is not easy to use watercolor this way. Other subjects included in the show were a cougar, moose, raccoon, red fox, lynx, meadow vole, mourning cloak and yellow sulphur butterflies, luna moth, swamp iris, and other living things, demonstrating Glen Loates' remarkable versatility.

When one refers to the exquisite quality of a piece of art, the usual definition of that over-used adjective comes to mind: beautifully made or designed. Applying that descriptive term to the watercolors of Martin Glen Loates is almost a necessity in order to convey adequately the degree of appreciation that his work arouses. However, the word exquisite itself is derived from the Latin exquisite, chosen, exquisite, from the past participle of exquirere, to search out. It is this shade, then, of the word exquisite that makes the adjective singularly appropriate in a more arcane sense to Loates' work. He has searched out and chosen the subtle gradation in color, the elegant rhythm in form and line, the elusive in mood. His Ruby-throated Hummingbird, as light as the pendant columbine blossoms that attract it, is part of the aura of a summer day, and more: it imparts that clean, verdant, colorful sparkle that characterizes what a summer day is. The artist has managed to illustrate, then to evoke, then to invite, finally to captivate.

Loates' common woodchuck, perhaps the pièce de résistance of the show, took this reviewer back in time. In childhood, we lay on our stomachs in summer clover, and some cool, green, crushed-grass deliciousness about that delightfully lazy pastime flooded back, immediately, upon seeing this brown, furry fellow standing in the grass, his black front toes clasping a crisp leaf. Many visitors to the exhibit commented on the fur – rich, thick, rendered perfectly, golden brown about the shoulders, greyed out from his whiskered nose, and forming an easily recognizable whorl down the center of the abdomen. Passing a hand down that soft belly, one would enjoy those fine thistle-down patterns of fur. Art, good art, encourages the viewer to imagine tactile possibilities. (The likelihood that the woodchuck would permit such familiarity belongs to another discussion.) Some zoologists have commented that Loates' mammal paintings are among the best they have ever seen. One of the nicest things about his way with mammals, incidentally, is his shrewd ability to avoid the "cute." To do this, one must know the animal very well, paint it accurately, allowing it the dignity of its usual activities, such as standing in a patch of grass eating a leaf, rather than portraying an antic pose that is more beguiling and less characteristic. Loates' pencil drawing of a Ruffed Grouse shows this game bird in his most dramatic moment: his neck feathers raised in a ring about his head, his tail erect like a turkey cock's, his mien admirably commanding and threatening as he mounts his drumming log. Loates uses soft pencil well and proves that black and white can be more colorful than color. The challenge in this medium is to use shadow, light, coarseness, delicacy, and roughness in a kind of orchestration that satisfies so sensually that color would be redundant. In central New York, the Northern (Baltimore) Orioles usually arrive in early May. Glen Loates has painted a pair of these familiar birds, known for their craftsmanship in nest-building. Perched at their pendant nest in the drooping branches of a tree, the pair is caught in the midst of brisk business – nest building. Later, they will browse for their food near the ground and on lush clumps of sweet fern. The underside of the male is bright orange, changing to an ochre color just under the rump. The female wears more subdued colors, her yellowish olive upper parts not so sartorially exciting as the sharp black uppers of her mate. Melodious describes the interplay of colors and tones in this watercolor: Pale, pale green leaves twist to give us deeper green shadows. We rivet upon the vibrant orange of the male, go on to the incredible intricacy of the soft gray nest that occupies the center of the painting, read the female as a more restrained accent in her olive green and dull orange. A caterpillar, later destined to be an oriole's meal, has done a random job on the leaves of this hanging branch. These holes are carefully observed, delineated as painstakingly as the coverts on the birds' wings, and treated as important elements in the total design. The white background of the painting is put to work by the laced leaves, not by accident but by conscious manipulation of negative spaces. Good designers may become great artists; great artists are always good designers. Without going into more detail, Loates' show includes a very small painting of a Snow Goose landing; there is a shadow in the softest shade of gray, cast by its strong neck against the straining pectoral muscles as it comes down to land, which is typical of Loates' meticulous observation and technical proficiency. The effect of the gray shadow is evanescent. It is not easy to use watercolor this way. Other subjects included in the show were a cougar, moose, raccoon, red fox, lynx, meadow vole, mourning cloak and yellow sulphur butterflies, luna moth, swamp iris, and other living things, demonstrating Glen Loates' remarkable versatility.

Our art prints are produced on acid-free paper using archival inks to guarantee that they last a lifetime without fading or loss of color. All art prints include a 1" white border around the image to allow for future framing and matting if desired.